Is the cost of living cheaper today than 80 years ago?

I recently came across a copy of The Telegraph from December 1936. I immediately looked at the prices of things.

1936 is the year of King Edwards abdication and the Jarrow Marches.

First off, The Telegraph in 1936 cost 1d. That of course is “old money” in the UK, and there were 240 d’s to the pound. The Telegraph carried advertisements on its front and back pages. On the front were travel ads, mostly ships departing to various parts of the Empire. On the back were adverts for housing, new build apartments in Central London, mostly. A cursory look at these prices was quite revealing. But first, the money.

Old Money and New Money

It’s a metaphor that’s still used in the UK, to mean anything that might have existed before and after a change. Before “decimalisation”, the UK’s monetary system had 20 shillings to the pound and 12 pennies to the shilling. Coins included the “half crown” (2 shillings and 6 pence), the “sixpence” and the “thruppeny bit” (three pence). That all changed in 1971 when “new money” became legal tender. As a child I found this exciting not to mention simpler to understand. But I also felt a sadness that the 13-sided thruppeny bit and the large “half crown” ceased to be legal tender, although the sixpence lasted a little longer with a value of 2.5 new pence. I was never fortunate enough to own a “ten shilling note” (50p) let alone any pound notes or higher. Bank of England pound notes no longer exist either, having been replaced by the pound coin in 1983, with no change in value.

Wages

In 1936, annual wages for many in the cities were around £130, with the national average across all sectors at £153 source: Measuring Worth. Agricultural workers were paid much less – more like £80. Industrial wages were of the order of £100 per annum. Female workers in 1936 would likely earn much less than their male contemporaries, perhaps as little as half as much for doing a similar job.

Today, farm workers with basic experience earn around £13,000 per annum. That’s about 160 times the 1936 levels. Average wages are around £26,000, 200 times 1936 levels.

Travel

Travel out of the UK in 1936 was almost entirely by ship. A “passage to India” started at around £40 and a return to New Zealand would set you back £130. That would be for “steerage class”. Travel in first class unsurprisingly comes in at a large premium.

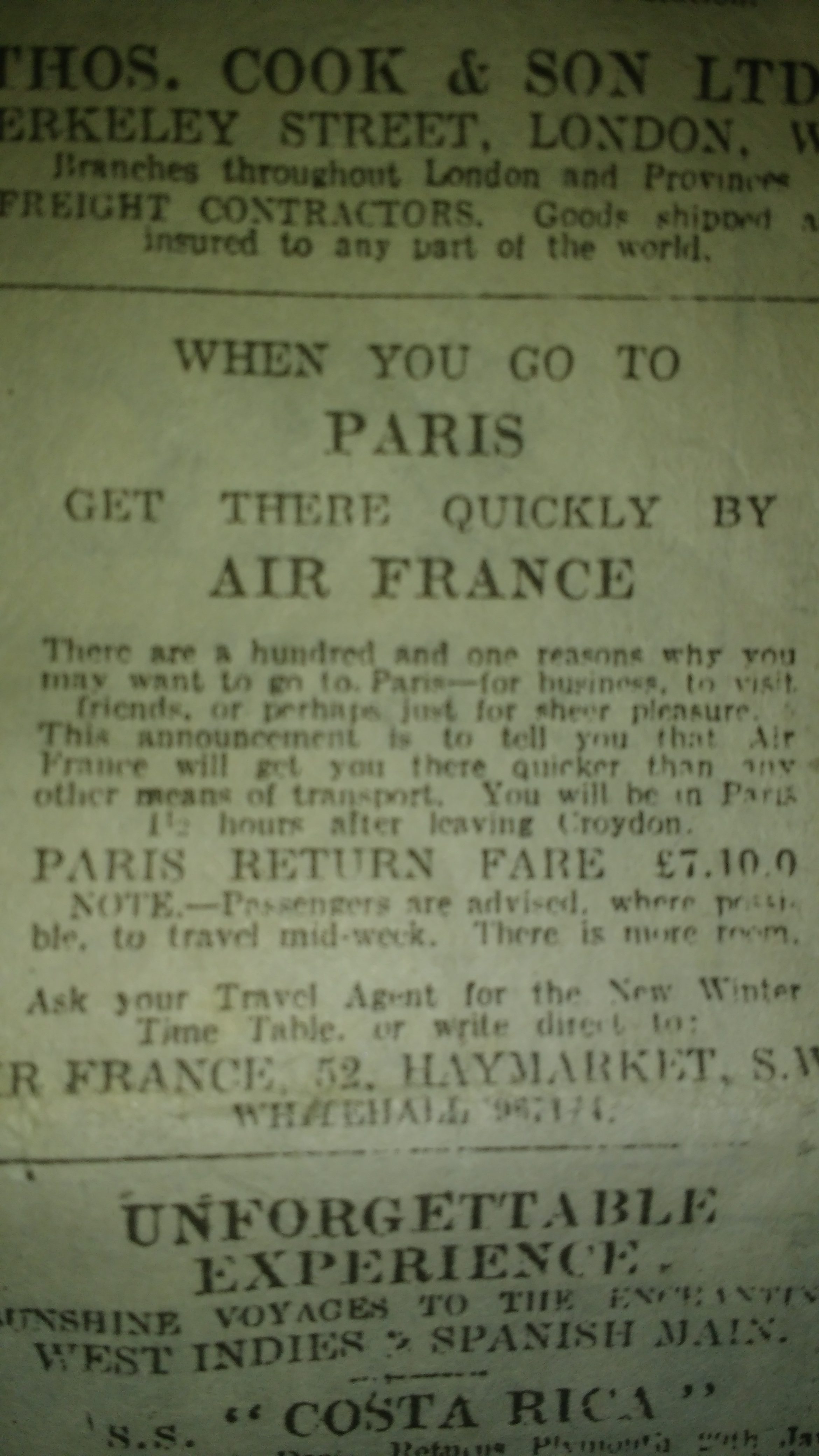

Air travel had started. One advert offered return Air France flights from Croydon Aerodrome (in what is now South London) to Paris (airport unspecified, probably Le Bourget). The cost, £7.10s. That’s shillings, 20 to the pound, so £7.50 in “new money”.

Comparing 1936 prices to 2016 prices is not easy. Ryanair might argue that it offers fares at £7.50 today before taxes and other charges are added. In which case air travel is effectively some 200 times more affordable today than in 1936. Flights to New Zealand vary a lot in price, depending on time of travel and how far in advance the tickets are bought. I paid £1700 for a return flight to Christchurch over Christmas 2014. Flights in January were, admittedly, cheaper. So let’s say that compared with the ships of 1936, New Zealand is about 10 times as expensive today as it was then, which actually makes it about 20 times as affordable!

Property

The 1920s and 1930s saw the expansion of suburbia. Before post-war housing estates, typified by cul-de-sacs with thematic road names, pre-war housing was along main roads and side streets with a more purposeful feel to them. Car ownership was not widespread, so access to public transport was much more important than it is today.

The 1936 Telegraph advertises apartments in central London for rent. Examples are (per annum):

- Park West, Marble Arch, 1-5 rooms, £95-320

- Arthur Court, Hyde Park, £100-£325

- Fairacres, Roehampton Lane, “House on one floor”, £325

- Bryanston Square, Marble Arch, “Commodious Family Flats”, £400-£550

- Hartington Court, SW1, £104

These properties might have been state-of-the-art in 1936 but today they might feel rather dated and tired. Nevertheless, a one bedroom flat in Park West is currently on the rental market for £395 per week, a two-bedroom flat in Arthur Court is on the market at £950 per week. The more expensive “house on one floor” in Roehampton Lane is advertised at £600 per week. In terms of pounds sterling, rent today is of the order of 100-200 times what it was in 1936, with the cheaper properties rising faster in rental value than the more expensive ones. Interesting to note that the rent charged on these properties has risen in line with average wages over the past 80 years.

Newspapers

Interesting to note that the Telegraph cost just 1d in 1936. Today it costs £1.40, yet over the internet it costs nothing! So the Telegraph has risen by a factor of 336 over the last 80 years. Arguably, however, there is much more content in the Telegraph today than there was in 1936.

Relative Inflation

As anyone reading my articles might have gathered, I am no big fan of specifying a good’s or a service’s worth in terms of currency. For me, currency itself has a value which is measured partly by what it can be exchanged for ans partly by the amount of tax demanded by the government. I would rather look at relative inflation, i.e. how much one good’s or service’s value has changed relative to another. We keep currency out of the equation then.

Of course, currency can’t be totally ignored. It’s the unit of value in which we are paid, and good and services become less affordable when their prices rise.

The 200 times increase in wages and the 200 times increase in London rents over 80 years suggests that there is no relative inflation between these two rates. And when we deal with averages, that is certainly true. Just as few could afford central London rents in 1936, so today can few afford them. But what these figures hide is the rise in lower-end prices. While rents for prestigious properties, both then and now, cost a whole year of the average wage earner’s salary, the affordability of lower-end properties (which don’t make it into the Telegraph classified ads of 1936!) has risen by much more. Rental prices are hard to find, but the values of properties themselves are more revealing. In 1936 the average price of a house was £550 but in 2016 this had risen to about £214,000. This is a factor of 400, double the rise in average earnings. As an aside, the Evening Standard calculate a 491-times increase during the Queen’s lifetime.

Another study sees London property prices rising much faster than the national average. This study in the Independent looks at the prices of houses in streets on the Monopoly board. An Old Kent Road house has risen some 3000 times its value in 1936. In Mayfair, it’s more like 4000 times.

Air travel, on the other hand, is cheaper today than it was back in 1936. A price of £7.10s would be a month’s pay or more for the lowest paid whereas now a flight to Paris would cost no more than a few hours’ work.

Goods and services which don’t make the 1936 Telegraph are more affordable, such as food and clothing, mostly due to imports and mass production. So the moral of the story is: invest in property to future-proof your wealth and lat the consumables look after themselves.