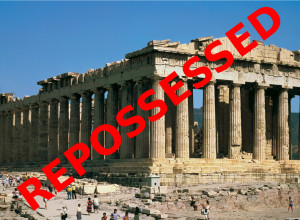

Greece, its Debt and the Euro

Greece has till the end on June to find 1.6 billion euros of debt repayment

In theory, at least. Perhaps the payment will be rescheduled (read delayed), perhaps Greece will be lent more money so it can repay this obligation. Some have likened this to “kicking the can down the road”. Or maybe Greece will default on its debt repayment, fail in its obligations to keep the euro and again in theory, be forced to leave the EU.

How did Greece get here?

All was well when Greece joined the euro, but as Europe went into recession, Greece was hit particularly hard. Recessions mean lower income tax revenues and consequently higher budget deficits. And with Greece’s relatively high spending per capita – particularly on its unfunded pensions (public sector) – there was simply not enough money left to pay interest on its debts. And given Greece’s falling creditworthiness, any new debts would come at higher levels on interest. The ECB and IMF did lend money to Greece to pay debts and debt interest but they insisted that Greece did something about its level of spending so that they could be more sure of being repaid. The consequent “austerity” was resisted by many in Greece, eventually leading to a change of government with the anti-austerity party Syriza coming to power. Syriza refused to accept austerity and only just managed to pay debt obligations in May 2015 through money held by regional and city governments. The 1.6 billion euros due at the end of June – some of which is already late – doesn’t look like it’s there, and the ECB and IMF won’t help out any more unless Syriza agrees to more austerity. It’s not quite stalemate, but almost. More like brinkmanship, with each side hoping the other would cave. Just today, Donald Tusk, EU Council President, commented:

“The game of chicken needs to end, and so does the blame game. There is no time for more games.”

“We need to get rid of the illusion that there will be a magic solution at the leaders level. This summit will not be the final step – there will be no detailed technical negotiations, that remains the job of the finance ministers.

“We are close to the point where the Greek government will have to choose to accept what I believe is a good offer for support, or to head towards default. At the end of the day, this can only be a Greek decision. There is time, but only a few days. Let us use them wisely.”

If Greece really doesn’t pay?

We can tell if a situation is important, because a word is invented for it. That word is Grexit – short for Greek exit. Or is it Greek-default-and-euro-exit? Never mind.

Interestingly, I can’t find anything that suggests a Grexit is an automatic consequence of a default, even if the default is to the ECB, the European Central Bank which creates the euros in the first instance.

In practice, however, Greek banks are owed billions of Euros by their government. And Greeks are withdrawing money at faster rates, fearing that their banks will collapse. The ECB has provided some short-term funding to keep the banks going but they really need to have reserves of proper long-term money. The banks could limit withdrawals, to prevent a run, but this contravenes the principles of the euro. One person’s euro is as convertible as another’s, so unless a temporary measure was agreed (this happened in Cyprus) the money will just keep on flowing out.

One solution is that the Greek government prints more money. But it’s not allowed to print euros, hence the solution of a Grexit is quite a neat one. The government repays the banks in drachma (or whatever the new currency is called) and the banks convert customers’ accounts to drachma too. Problem solved.

Problem not solved. The internal problem, yes, but lenders outside of Greece will still want their euros back. The drachma/euro exchange rate will likely fall well below its initial 1:1 making debt repayments even more expensive than they already are. So Greece’s current debt, at 175% of GDP (compared with around 100% for the USA, 90% UK and 80% Germany) might rise to levels much higher than that, and may never be repaid. This will likely mean international debt markets will be closed to Greece, although Russia is thought to be considering financial help in return for who knows what.

If Greece really wants to stay in the Euro

It has two options:

- Accept the austerity conditions, like pension reductions and welfare cuts, and use money promised by the ECB and IMF to repay its June debts.

- Find a way to keep its banking system afloat, perhaps with Russian money if their conditions are more palatable than those of the ECB and IMF.

As always, it’s not black and white. The EU does not want to see Greece leave the euro. Technically it means Greece must also leave the EU, which runs counter to that organisation’s aspirations. But even if that’s fudged over, an EU exit will question the sustainability of the single currency project.

Russia? Really?

Again, we don’t know whether Greece is embarking on some Russian-inspired maskirovka or if what we see is what we get. What we do know is that Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras is meeting Mr Putin today. Expect some noises over the next few days as the EU decides whether to call Tsipras’ bluff on this or to ease the ECB’s conditions for a bailout.

What of the Greek people?

Indeed. Most of the analysis is technical, concerning obligations which were agreed by a small number of people on behalf of many. Why should people in Greece suffer simply because they happen to be in Greece?

One side of the argument is that Greeks are paying the price of poor financial management by their government; for tax evasion by wealthy Greeks; and for onerous conditions forced on them by the ECB and IMF. The other side goes something like: you elected this government and it’s a democracy, so you have to live with the consequences.

Converting people’s euros to drachma sounds, well, illegal. But governments can do things like that. And with the drachma falling against the euro, if for no other reason than the government will want to inflate their way out of debt by printing more money, imports will feel very expensive. On the other hand, there should be an export boom of Greek goods – and holidays – giving Greeks the chance to earn some foreign currency.

People aren’t stupid, though. Given that 4 billion euros is being withdrawn from Greek banks this week alone, there will be plenty of foreign currency about should there be a Grexit. Those holding euros (or dollars or gold or bitcoin) will be the wealthy ones.

What about other countries?

Other heavily indebted countries could be caught with the “contagion” of a Greek default. Those exposed the most to Greek debt will themselves be poorer and their own debt repayments might be at risk. Portugal and Ireland, two countries which commentators have singled out, both claim that they can withstand a Grexit.

But this does raise a general question about national debt, and whether a country is liable for its repayment if the debt was created undemocratically. There are countries around the world paying billions of dollars of debt which was raised and spent corruptly by dictators. What right has the lender to demand that successors pay back these ill-gotten gains? Perhaps there is a political reason, about which we can only speculate.