UK pension reform – what happens next?

Until recently, the 2000s have seen some major pension reforms. What might the next development be?

UK pensions used to be quite dull things. There were workplace pensions, usually based on final salary and years worked, paid for by an employer’s pension fund or by the state. And there were private pensions, and Additional Voluntary Contributions (AVCs), based on defined contribution (DC) and basically a tax-efficient investment scheme.

Until 2006, people could contribute to a private pension or AVC, or FSAVC (like an AVC but through a private pension provider, not the employer) to the extent of a percentage of their gross earnings each year. There was an absolute annual cap on this contribution, which was £105,600 in 2006. This prevented those on very high income benefiting from large tax rebates. Because the way these pensions worked was that tax already paid to the Inland Revenue (now HMRC) would be reclaimed, the saver simply handing over a cheque for the net equivalent.

Brown’s reforms

In 2006, chancellor Gordon Brown changed the rules. Rather than limiting annual contributions to a percentage of annual gross income, there was now a lifetime allowance which was the same for everyone. This was perceived to be a fairer way of regulating contributions, as those on low incomes wanting to save more than their tax free allowance (15% at one point) could not do so but those on higher income could save that same amount. The £1.5m lifetime allowance sounded very generous, and perhaps it was.

Osborne’s reforms

After the 2010 general election, a Conservative-led government had George Osborne as chancellor. He initially increased the lifetime allowance to £1.8m but then incrementally reduced it down to £1.0m where it remains today. He also capped the annual contribution at £50,000 before reducing that further to £40,000, subject to that being no more than 100% of taxable earnings. (i.e. you can’t claim back more tax that you have paid, although low earners can save £3,600 even if they earn less than that).

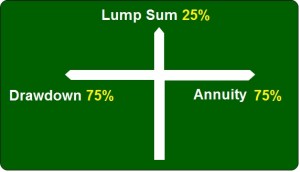

More importantly, in 2015 Osborne freed up what could be done with a DC pension. Prior to that, it could only be used to buy an annuity at retirement. In other words, you hand over your DC pension pot and in return the annuity provider pays you so much per year. The “so much” depended on the prevailing annuity rates in the market, which in turn were connected to interest rates. Under Osborne’s pension freedom, anyone over 55 could cash in some or all of their pension savings. 25% of that would be tax free, with tax being payable on the remainder (unless it was used to buy an annuity). Further, the pension pot could be “crystalised”. This means you can take 25% tax free and leave the remaining 75% to provide taxable income each year. This is likely to be more tax efficient than leaving the fund “uncrystalised” where that same withdrawal would be subject to tax on 75% of its value. This set of diagrams is a useful illustration of how the pension regime works at retirement.

Another interesting reform is that pension investments (unlike annuities) can be passed on to nominated beneficiaries after death. They will, however, be taxed as income.

Osborne really wanted to change the tax status of pension funds completely. Rather than claiming tax back from HMRC on each contribution, savings would be taken from taxed income only. But there would be no tax on drawdown after retirement. Pensions and ISAs would be largely the same vehicles. But few trusted a future government not to introduce tax on the way out too. Osborne lost his job as chancellor in 2016 and there have been no further reforms.

Lifetime allowance

Key to current pension legislation is the Lifetime Allowance. Once as high as £1.8m, it is now £1.0m. Is that generous? Not as much as it sounds. First, it includes workplace pensions. And if that is a final salary scheme, the value of the pension pot is considered to be 20 times the annual pension. So anyone due to receive a pension of £50,000 will already be at their Lifetime Allowance, meaning tax will be payable on any additional pension savings.

Where does the value of 20 come from? Again, it’s back to annuity rates. Indeed on that basis, 20 sounds quite generous. However when the Lifetime Allowance came in in 2006, the factor was only 10 because interest rates and consequently annuity rates were higher, and the lifetime allowance was £1.8m. Our £50,000 pensioner would have had a pot worth £500,000, and could add to that another £1.3m of DC savings if they could have funded it.

Annuities

A combination of Osborne’s pension freedoms and low interest rates have meant the market for annuities has fallen. In fact earlier this year, the number of annuity providers had dropped to seven. Current annuity rates are still around 20, despite the absurdly low base rate of 0.25%, or around £5,000 annually for every £100,000 invested.

This is poor value for the new pensioner. Some say government should raise interest rates for that reason, but that’s simply making government debt more expensive to help pensioners. As things stand, it’s likely to be better to have a pension as a drawdown fund than to buy an annuity. Pension providers offer this service now, or anyone who self-invests via a SIPP can access their fund in drawdown and continue to manage its assets.

It might even be worth cashing in a final salary pension, whose value is based on annuity rates.

What next for pension reform bad news?

The next iteration is likely to be less favourable to the future pensioner. Here’s a list of restrictions a chancellor might place on pensions:

- Reducing or removing the 25% tax free allowance. It’s hard to understand why this was available in the first place. The temptation to claw some or all of it back would be an easy decision.

- Further restrictions on tax-free contributions. The highest earners have already seen their options curtailed. We can probably expect the amount of tax reclaimable and/or the maximum tax-free annual contribution reduced.

- Further reducing the Lifetime Allowance. Can it go down further, when annuity rates are worsening? That’s been the trend, so don’t discount it.

The case for further positive reform

Let us first consider what a private pension actually achieves. Taxed income is invested in the pension fund and after reclaiming the tax already paid, is effectively a gross investment. The investment (hopefully) grows then at some later date it’s withdrawn, and subjected to tax. Consequently it’s not tax avoidance. It’s tax deferral.

So why have a Lifetime Allowance? That’s a good question. It sounds like the government are just being awkward. They want their tax now rather than later, most probably, to make the deficit figures look better that they otherwise would. That’s a false piece of statistics, as tax collected in years to come is effectively a state asset with a present value, and could in theory be included in deficit calculations like a company would include outstanding debt owed to it on their balance sheet. I would advocate scrapping the Lifetime Allowance completely, especially since a further worsening in annuity rates, or even a decent pay rise, will affect the imputed value of a final salary scheme used in the calculations.

Linked to the Lifetime Allowance is the annual contribution cap. This is currently £40,000. And again I wonder why it needs to be there at all, given that pensions are not tax avoidance, they are tax deferral. If I get a large bonus from my employer, why shouldn’t I be able to put it away for my retirement to be taxed later, rather than pay 40% tax on it now? I know it’s a nice problem to have, but the solution can still be fair.

Finally, Gordon Brown’s taxation of dividends held by pension funds (at 10%) amounts to double taxation, as subsequent pension income will be taxed also. Maybe it’s time to recognise that what might have looked clever 20 years ago, looks less clever today.

Positive reforms don’t necessarily mean better deals for pension savers. They might mean that everyone benefits through de-skewing tax treatments that favour the wealthy. The CPS points out that while higher rate taxpayers can pay into private pensions while reclaiming the 40% tax, many subsequently only end up paying lower rate tax when they draw down their pensions. Scrapping higher rate tax relief would save the nation £7bn annually. The CPS also suggests reinstating the dividend tax relief and changing the 25% tax free lump sum into a 5% pension top-up. The tax anomaly ony arises because the UK has progressive taxation rather than a flat tax.

Money Questioner’s summing up

Pension tax relief is really tax deferral. But because our tax system allows us to take advantage of tax allowances and tax bands, a high rate of tax saved today can be spread out over many years of retirement at a lower tax rate (or even none at all). This, I believe, is the fault of our tax system rather than our pensions regime. However in the absence of a flat tax, there is a compelling logic for scrapping higher rate tax relief.

If that’s happening, then that’s a more compelling reason to remove annual contribution limits and lifetime allowances. They will be less attractive to higher rate taxpayers anyway, if only basic rate tax can be reclaimed. And they help to encourage people to save more for later in life when their annual taxable income is volatile.

Although I hope to benefit one day from the 25% tax free lump sum, it really is hard to justify. As things stand, the most tax-efficient way to manage a pension pot in retirement is to take the 25% tax free lump sum as soon as possible then to place the remaining 75% in drawdown.

“I hope to benefit one day from the 25% tax free lump sum, it really is hard to justify”

I am in the same boat, I really hope the 25% lump sum is there. But, really it makes no sense other than for bribing pensioners.

Do you think that the lowering of both the annual contribution & lifetime limit forces better off people to invest in other assets such as buy to let? £40k year pension might not feel like much for someone earning £100k/year. Have these people been guided into buying houses instead? Should we not have allowed a higher pension limit and instead held shares in Apple/Amazon/Alphabet instead of pushing up UK house prices?

I think that’s right. The best and safest investment in recent years has been residential property, and it makes sense for someone with a large income to become a buy-to-let landlord when they retire. I know that the 25% lump sum has been used by some for that purpose too.

I would like to see the annual contribution limit removed and the lifetime limit raised, perhaps in return for capping the 25% tax free amount so that pensioners with small pots aren’t penalised. A cap of £250,000 is more than enough and consistent with the current £1m lifetime limit. Hard to know if that will tempt savers into pensions rather than property, but certainly worth considering.

Gordon Brown once entertained the idea of residential property in a SIPP, but rejected it. That would have been worse!

“I would like to see the annual contribution limit removed and the lifetime limit raised”

Personally, I think that both are not needed. The lifetime limit is an odd thing with such a low annual contribution limit.

Although I don’t believe in property as an investment – because it will simply gain income at someone else’s expense in addition to pushing up property prices. I am going to play the game and invest in property. This is partly due to the lifetime limit and partly because I can’t trust the government not to meddle with the conditions surrounding my SIPP. If there was no lifetime limit and if I knew the SIPP rules were not going to change, then I would not be investing in residential property.

Sorry to keep rambling on. I am also going to put another suggestion out there as to why the lifetime limit is bad. a £million pension would give someone £40k/year, which is nice, but it’s not really rich. If I somehow manage to hit the limit before I am 65, what should I do? The obvious thing would be to retire! But, maybe the UK needs more workers. So, if there was no limit, I may be tempted to work for longer. But anyone hitting the limit would be a fool to do so.