Why new council housing is right for the UK

Theresa May announces 25,000 new council homes in the biggest programme since the 1970s

The announcement of 25,000 new council homes came during the prime minister’s speech at the Conservative Party Conference. From the Thatcher government onwards, council housing has been seen as a state-sponsored solution to what should be a private sector market problem. Council homes have been sold to their tenants at discounts in order to boost private ownership, in keeping with what we now call neo-liberal ideals.

So is this a u-turn on neo-liberalism? I would say not. And here’s why.

The state spends £24 billion each year on housing benefit

Housing benefit is paid to the less well off in order that they can afford a place to live. This money never really touches their pockets, rather it is paid to landlords in either the private or the public sector. And as rents rise, so does the cost of housing benefit.

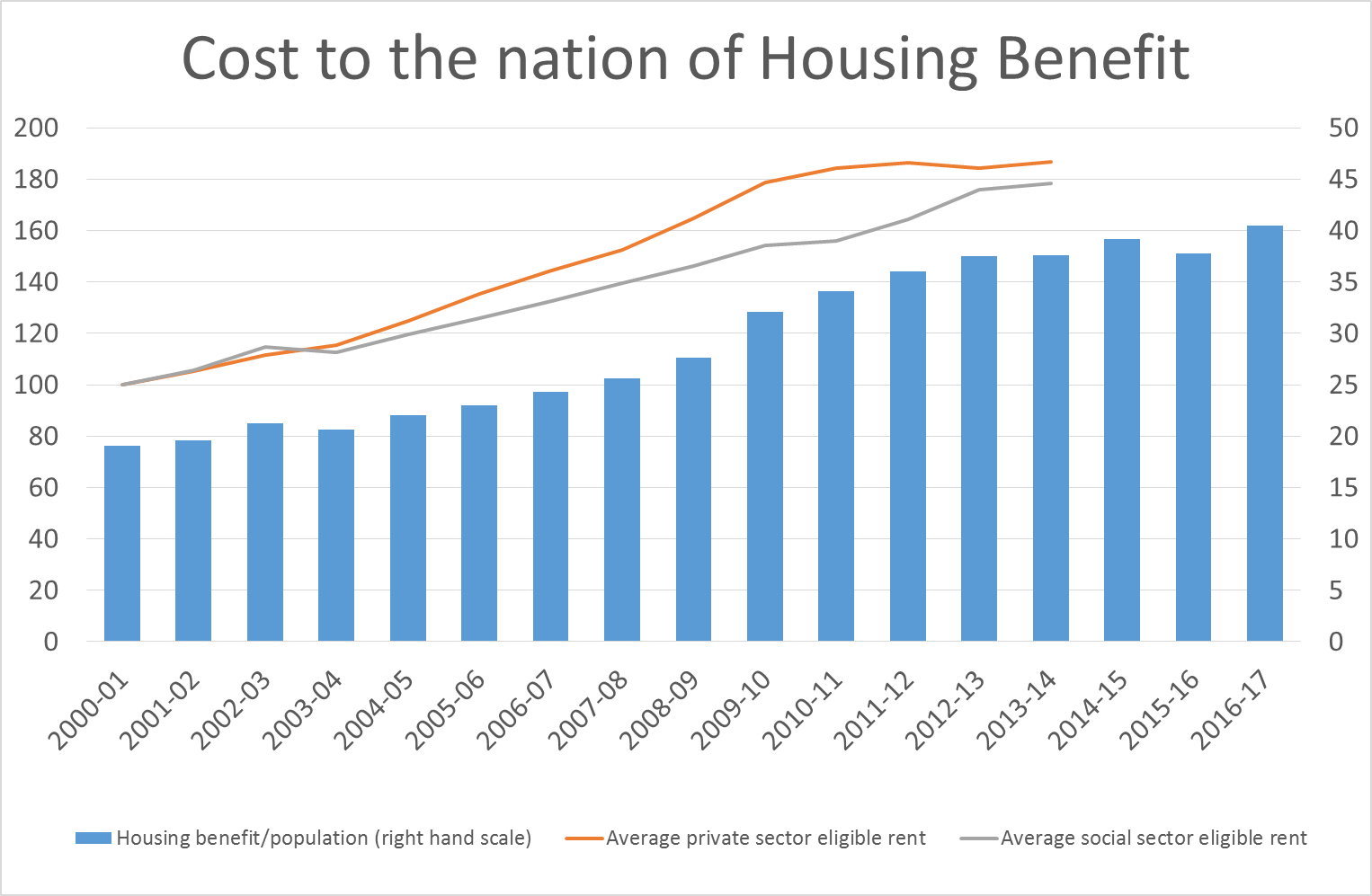

The chart below shows the cost of rent, based to 100 in the 2000-2001 period, as applied to housing benefit. This is “eligible rent”, so excludes penthouses and holiday cottages. It also shows the cost to the nation of housing benefit. I have divided this by the UK population and scaled it by 1m) in each year to remove the effects of population growth. Without this, the rise would be steeper still. We can see that the trends are closely related, as we might have predicted. Both have nearly doubled over the period (I don’t have figures for the rent indices after 2014 but anecdotally, we know rent has continued to rise).

Sources: OBR, ONS and DWP

The state is the biggest single buyer of rental accommodation

£24 billion is a lot of money going into the rental market. This begs the question: Is the nation getting the best deal it can here?

Let’s look at this a bit differently. If you or I had access to cheap finance, would we buy a place to live or would we rent? Most of us would go for the former, and many of us are doing so not just for ourselves but for our children too. It fixes the outgoings rather than couples future liabilities to what must surely be a inescapable trend for house price and consequently rent inflation.

The same surely applies to the state. Can the state get better value for money housing its beneficiaries or paying for others to do so? Again, surely the former applies. Consequently it makes sense for the state to be both landlord and tenant. This is especially true for the state, including local authorities, because it also owns undeveloped land for which the incremental cost of building new homes means it is more cost effective than going to the market with such high demand and pushing prices up further.

A return to socialist policies?

Absolutely not. While socialism is quite comfortable with social housing, the point of this exercise is for the state to get the best deal it can get in the market. Just like a private individual might choose to build (or buy a new-build) rather than rent, so might the state. It’s about choice, and I would prefer that the state uses my taxes wisely and competitively.

How much difference will 25,000 houses make?

With around 5 million claimants, the majority of which are already in social housing (council or housing association), 25,000 doesn’t sound like much of a dent. And it’s not. On the other hand, an increase in rental housing supply will help to bring down rent in the private sector. There will be a “sweet spot” somewhere, where the cost to build and let new council homes and the present cost of future private rents are about the same. That probably means more than 25,000 homes, but we can’t really predict how many.

Conclusions

New council houses will help the state in two ways. First, to save on the ever-rising costs of paying housing benefit to the private sector. And second, to increase the supply of rental accommodation generally, which will actually conspire to reduce private rents with its reduced demand.

Ironically, the announcement comes on the back of a £10bn injection through Help to Buy, which many acknowledge to be inflationary. So it’s anyone’s guess where the housing market goes from here.