Taxman – 50 years of the Beatles’ Revolver

Let me tell you how it will be. There’s one for you, nineteen for me.

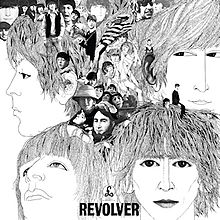

That is the opening line from Taxman. Taxman is the opening track on The Beatles’ seventh studio album, Revolver. Released on 5 August 1966, Revolver is considered by a large number of Beatles fans to be their finest album. It spent seven weeks at number one and 34 weeks in the album chart in total. It also marked the end of The Beatles’ touring days, these new recordings being more complex than those on previous albums.

Although I was too young to remember its release, I recall hearing it for the first time when a Beatles-loving friend of mine in the late 1970s put it on. This wasn’t The Beatles as I knew them. I knew the early songs, typified by young women screaming at the four well-dressed identikit players on the stage. And I knew some of the later songs like All You Need is Love. But only one from Revolver – Yellow Submarine. The sophistication of the music and lyrics on Revolver was perhaps first hinted at on Rubber Soul, but Revolver certainly cemented the Beatles’ claim to be part of tradition that was to become British progressive rock music. That means prosaic lyrics, musical influences from classical and Eastern arrangements, and experimental recording techniques. This against the backdrop of the rock’n’roll, blues and country influences that typifies US rock music and indeed some of the Beatles’ music to date.

Revolver was no concept album, though. It was far too eclectic for that. A collection of songs written individually by different members of the band, and not necessarily featuring the whole band on each recording. If there is anything linking the songs, though, it’s that they tend to have a serious side to them. Apart from Yellow Submarine.

Indeed Yellow Submarine is an interesting track. Not because of its nonsense lyrics, redolent of The Owl and the Pussycat. But because it’s a whimsical addition to an otherwise serious album. Maybe this gave other musicians and bands permission to do the same, such as David Bowie’s The Laughing Gnome, or tracks such as Cream’s Mother’s Lament and ELP’s Benny the Bouncer.

Much has been written about the Beatles and indeed about Revolver, so I won’t concentrate any more on the album. But rather on the first track, because it has themes relevant to this blog.

Beatles and songs about Money

Taxman isn’t the only Beatles song about money. They also recorded (but didn’t write) Money, that’s what I want and (money)Can’t Buy me Love, which was written by Paul McCartney. But these songs weren’t political. Rather they compared money to love, one rather more cynically than the other.

Taxman

It’s probably only illegal uploads of the original Taxman which appear online, so here’s George Harrison singing Taxman in 1988 with Eric Clapton.

Musically, Taxman is interesting. Partly because it was a George Harrison song. And partly because Paul McCartney, not George, played the guitar riff. It sounds rather flat, and that’s deliberate. It’s played in the key of D major, but the C-sharp is flattened to C-natural, giving the song a sound which is kind of a conflation between D major and E minor. The opening riff was recycled by Paul Weller in The Jam’s 1980 hit Start.

The story behind Taxman goes that George Harrison found out that the prevailing tax rate for unearned income above a certain threshold was 95%. Which meant that for every £20 of income received, £19 was paid as tax. And when a musician gets angry, creativity follows. Of all The Beatles, George was the most financially attentive The opening lines:

Let me tell you how it will be

There’s one for you, nineteen for me

Cos I’m the taxman, yeah, I’m the taxman

describe exactly that. The taxman takes nineteen pounds in every twenty.

We might not feel too sorry for The Beatles, who were at the top of their game and were earning much more than most in the UK could only dream of. And to their credit, they didn’t leave the UK like other rock stars did, such as The Rolling Stones and David Bowie eventually did. In fact the top rate of tax was as high as 98% and indeed was briefly over 100%, once the “surtax” was added to income tax at 83%. It’s a curious thing that rock stars, usually associated with being anti-establishment and tending towards socialist politics, find themselves waxing lyrical against a socialist government.

The song continues as a rant, really. Lyrics like

If you get too cold I’ll tax the heat

If you take a walk, I’ll tax your feet

continue the theme of anger against the power the Taxman has to take whatever sums of money the government says he can take. And this continues to the end

And you’re working for no one but me

Is 95% tax unfair

Well, that’s a hard question to answer without reference to a set of values which guide us in a quest for an answer. There is such a thing as a “Laffer Curve”, which demonstrates how much tax revenue a government is likely to collect against the rate of income tax. If the tax rate is zero, the revenue is obviously zero. If the rate is 100% then the revenue is likely to be zero too, because why would anyone work if they weren’t going to keep any of their money? (OK some might). Somewhere in between is the sweet spot. But that’s unlikely to be 95%, even 95% above a certain threshold, which is what we’re really talking about. Wherever possible, those falling well above the threshold will relocate outside of the UK to avoid paying it, which really turns the 95% rate into a deterrent to wealthy people staying in the UK.

But Laffer Curves aside, 95% will bring in some income, including we presume George Harrison’s back in 1966. What is likely, though, is that the political climate at the time legitimised chasing high earners for large amount of tax, because “they don’t need it”.

Successive governments generally reduced top income tax rates, shifting emphasis onto indirect taxation, especially VAT. The Heath government reduced the 83% rate to 75% in 1971, still keeping the 15% investment income surcharge, or “surtax”. Although the Wilson government restored the 83% rate in 1974, this was cut to 60% in 1979 by the Thatcher government, with the surtax abolished in 1985. The top rate is currently 45% although it has been 40% and 50% at different times in recent years.

Some call for the return of the Investment Income Surcharge. Economist Richard Murphy, admired by Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, calls for a 75% rate of tax on investment income. In the USA, the Obama administration has placed a 3.8% surcharge on investment income to pay for Medicare.

Money Questioner’s response

I agree with George. 95% tax is crazy. In fact as I have articulated in the past, my own preference is for a flat tax rate, so everyone pays the same rate regardless of how much they earn or where it arises. However, before my left-of-centre friends start burning me at the stake, I would rather see the wealthy taxed according to their wealth rather than their income, which might be zero. The best way to do this is via a Land Value Tax, which can’t be avoided, unless someone manages to make their land invisible. We can also do away with transaction taxes such as Stamp Duty Land Tax and Inheritance Tax if we tax wealth in some way, so everyone pays not just those who move home or die.

The taxation of income has become an obsession, and progressive tax rates the norm. Consequently someone earning £1m in one year then nothing for nineteen pays far more in tax than someone earning £50,000 for twenty years. Isn’t tax such an easy thing to rant about?